Bayesian Reaction Optimization Using EDBO - Part III

Published:

Part III - Bayesian Reaction Optimization

In part I we installed the pre-release of EDBO and ran basic functionality tests. In part II we got a handle on some simple use cases for the software. In this post, we will see how to apply EDBO to chemical reaction optimization problems by automatically encoding a search space for a new problem and running a round of human-in-the-loop optimization. To start, we need to define exactly what problem we are trying to solve. Specifically we need to identify: (1) the objective, (2) where to search, and (3) our experimental capabilities.

The objective

The objective is what are you trying to optimize and as such it can have a big impact on your results. For example, if you are optimizing an enantioselective transformation you may be considering either enantiomeric excess or enantiomeric ratio as your target. In this context, enantiomeric ratio (or inferred $\Delta\Delta G^{TS}$) is preferable due to the established physical relationship between the ratio of enantiomers and the relative rates of the selectivity determining step. However, with this objective it is conceivable that the reaction could be optimized to deliver >90% ee but only 5% yield (and I have seen exactly this happen in some projects). Never the less, the optimizer would have very effectively carried out the task it was presented with.This in tern leads to the challenging (and ever present) situation in which perturbing the conditions to optimize yield can lead to a degradation in ee. Thus, in the context of single objective optimization it may be preferable to redefine your objective in a way that captures both objectives. For example, you could instead optimize the yield of the major enantiomer (inferred from the selectivity and the overall yield).

Where to search?

After we have identified our objective, we then need to define exactly what subset of plausible experiments (all possible catalysts, reagents, concentrations, temperatures, etc.) we should consider. This is a critical step because the identity of search space will ultimately determine the success of the campaign - if the space is too small we lower the chances of finding optimal conditions; if the search space is too large it may take longer to discover optimal conditions and modeling will require more computational resources. There are a number of approaches to this problem including simply drawing conditions from the literature, based on physical knowledge, and our experience or utilizing a less biased data driven approach such as unsupervised learning to select a subset of experiments which spans the larger search space. It general, I believe that we should utilize both approaches as a way to include conditions which fit our knowledge (a kind of chemists prior) and leave open the possibility for unexpected results. In order to stay on topic in this post I will not present any further discussion at this time. However, keep in mind that whatever our approach it is worth putting in the effort to (1) search the chemical literature for related reactions (e.g., SciFinder, Reaxys, etc.), (2) employ our knowledge and training as synthetic chemists, and (3) consider a broader hypothesis space that is less biased by our experience. For example, if you we optimizing a Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction we will want to include tried-and-tested ligands such as Buchwald-type phosphines as well as sample other diverse structures.

Experimental capabilities

Prior to starting an optimization campaign we should consider our experimental capabilities. For example, we need to decide the number of experiments to run in parallel (if any). It is also worth while to take the time to collect initial data using “obvious” experimental conditions as a baseline (e.g., if you are running a Ni/photoredox reaction, try dtbbpy as a ligand first). Of course, if you are interested in optimizing a reaction with EDBO you have likely already carried out initial experiments to test your hypothesis. Once we have initial data, it can be helpful to establish the error associated with the experiments by running duplicates and/or making a calibration curve. This information will give us an idea of what a meaningful improvement in the objective is and potentially enable us to calibrate the optimizers noise parameters.

Reaction optimization

OK, now that we have gotten the philosophical exposition out of the way we can get down to business and actually demonstrate the use of EDBO for reaction optimization. Let’s assume that we have already identified the objective, search space, and our experimental capabilities. We can then instantiate an optimizer that fits these decisions. The objective is defined by the signal you feed into the optimizer - here we use %yield of desired product. The experimental capabilities can be defined using key word arguments (e.g., batch_size=5 tells the optimizer you can run 5 experiments at a time). However, communicating the selected search space to the optimizer requires us to decide on a reaction representation.

Encoding the reaction space

We will represent our reaction(s) using a numerical encoding. This encoding could include ordered numerical dimensions (temperature, concentration, etc.), unfeaturized categorical descriptors (one-hot-encoding), and features which contain physical or chemical information about the experiments in the reaction space. EDBO has complete flexibility with respect to how you define the encoded search space.

Build it yourself: Of course the most flexible (and laborious) option is to build the search space yourself as a pandas DataFrame.

import pandas as pd

from edbo.bro import BO

from edbo.utils import Data

# Define dimensions

concentrations = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5]

temperatures = [0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100]

# Simple loop to build combinations

search_space = []

for c in concentrations:

for t in temperatures:

search_space.append([c,t])

domain = Data(pd.DataFrame(search_space, columns=['C', 'T']))

# The built in GP model requires normalization

domain.standardize(scaler='minmax', target=None)

# Instantiate BO object

bo = BO(domain=domain.data)

The models normalized domain can be accessed via the objective module:

bo.obj.domain.head()

| C | T | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.2 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.4 |

And the unnormalized domain can be accessed from the data container:

domain.base_data.head()

| C | T | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.1 | 10 |

| 2 | 0.1 | 20 |

| 3 | 0.1 | 30 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 40 |

The flexibility can be great if you are building a custom search space (e.g., with computed interaction terms). However, once we start to include chemical descriptors for categorical components this process can take a bit of work. In many cases, we can actually have EDBO build the search space automatically. Functions for building the search space can be found in the edbo.feature_utils module (e.g., reaction_space). We can check out the documentation using help(reaction_space).

Help on function reaction_space in module edbo.feature_utils:

reaction_space(component_dict, encoding={}, descriptor_matrices={}, clean=True, decorrelate=True, decorrelation_threshold=0.95, standardize=True)

Build a reaction space object form component lists.

Parameters

----------

reaction_components : dict

Dictionary of reaction components of the form:

Example

-------

Defining reaction components ::

{'A': [a1, a2, a3, ...],

'B': [b1, b2, b3, ...],

'C': [c1, c2, c3, ...],

.

'N': [n1, n2, n3, ...]}

Components can be specified as: (1) arbitrary names, (2) chemical

names or nicknames, (3) SMILES strings, or (4) numeric values.

encodings : dict

Dictionary of encodings with keys corresponding to reaction_components.

Encoding dictionary has the form:

Example

-------

Defining reaction encodings ::

{'A': 'resolve',

'B': 'ohe',

'C': 'smiles',

.

'N': 'numeric'}

Encodings can be specified as: ('resolve') resolve a compound name

using the NIH database and compute Mordred descriptors, ('ohe')

one-hot-encode, ('smiles') compute Mordred descriptors using a smiles

string, ('numeric') numerical reaction parameters are used as passed.

If no encoding is specified, the space will be automatically

one-hot-encoded.

descriptor_matrices : dict

Dictionary of descriptor matrices where keys correspond to

reaction_components and values are pandas.DataFrames.

Descriptor dictionary has the form:

Example

-------

User defined descriptor matrices ::

# DataFrame where the first column is the identifier (e.g., a SMILES string)

A = pd.DataFrame([....], columns=[...])

--------------------------------------------

A_SMILES | des1 | des2 | des3 | ...

--------------------------------------------

. . . . ...

. . . . ...

--------------------------------------------

# Dictionary of descriptor matrices defined as DataFrames

descriptor_matrices = {'A': A}

Note

----

If a key is present in both encoding and descriptor_matrices then

the descriptor matrix will take precedence.

clean : bool

If True, remove non-numeric and singular columns from the space.

decorrelate : bool

If True, iteratively remove features which are correlated with selected

descriptors.

decorrelation_threshold : float

Remove features which have a correlation coefficient greater than

specified value.

standardize : bool

If True, standardize descriptors on the unit hypercube.

Returns

----------

edbo.utils.Data

Reaction space data container.

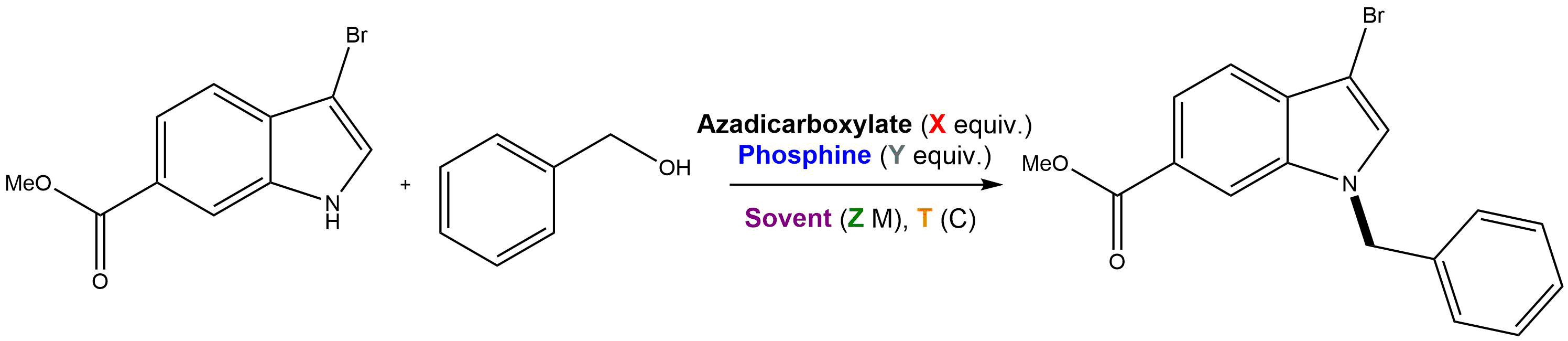

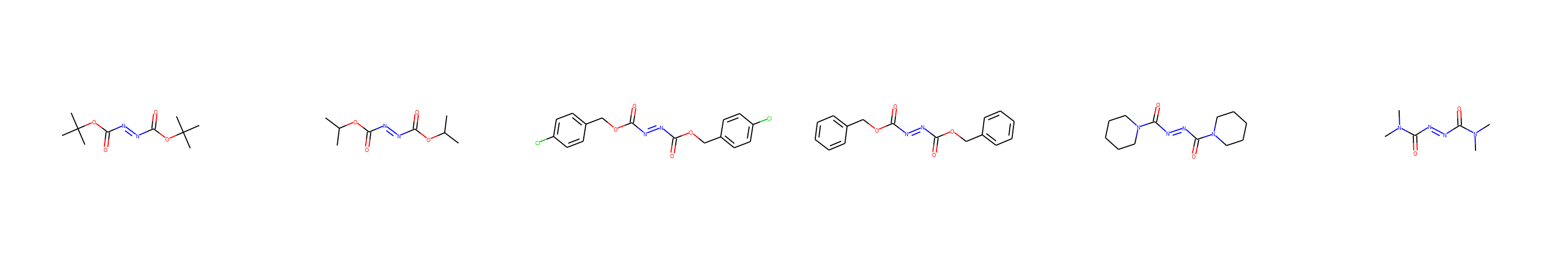

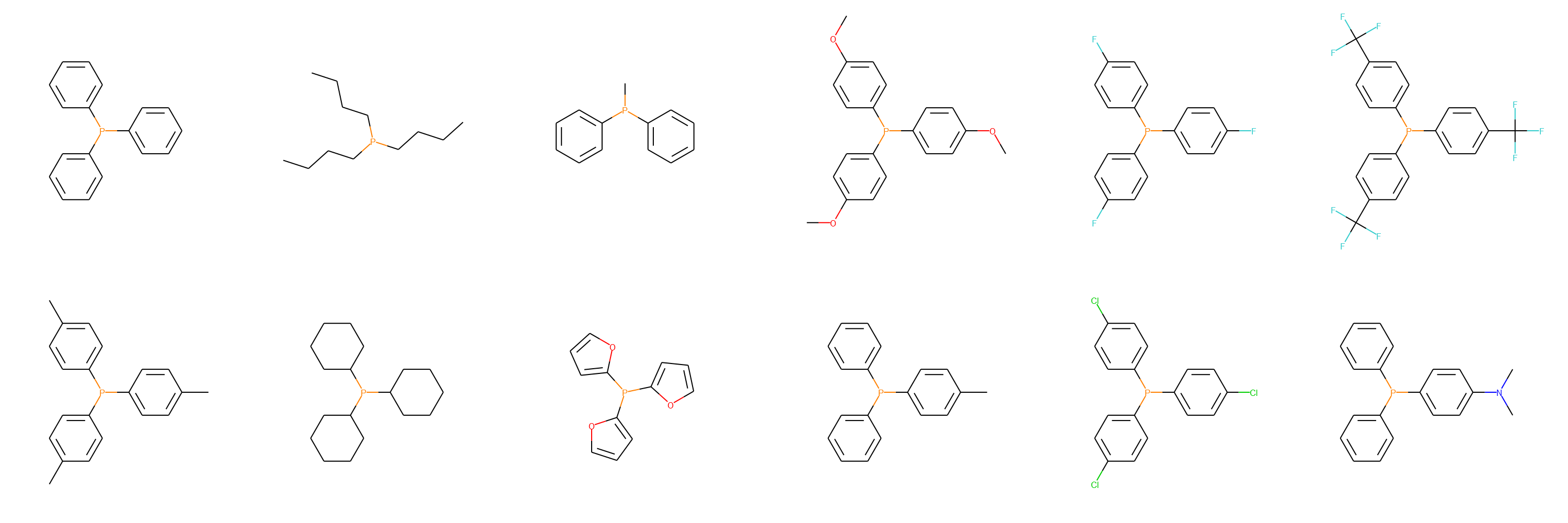

Automatic encoding with EDBO: You may have noticed in part II that we didn’t have to build search space DataFrame in our examples. This is because the BO_express class automates this step. Let’s check out an example. Suppose you are interested in optimizing a Mitsunobu reaction and you identify azadicarboxylate, phosphine, equivalents, solvent, substrate concentration, and temperature as important parameters. An example reaction scheme is below.

All we need to define in order to automatically encode our reaction is a dictionary of components and a dictionary of the desired encodings. Using BO_express in this way will encode, clean, decorrelate, and normalize the reaction space.

from edbo.bro import BO_express

# (0) Define possible settings of each reaction parameter

azadicarboxylate_SMILES = ['CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C',

'CC(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)C)=O)=O)C',

'ClC1=CC=C(COC(/N=N/C(OCC2=CC=C(Cl)C=C2)=O)=O)C=C1',

'O=C(OCC1=CC=CC=C1)/N=N/C(OCC2=CC=CC=C2)=O',

'O=C(N1CCCCC1)/N=N/C(N2CCCCC2)=O',

'CN(C(/N=N/C(N(C)C)=O)=O)C']

phosphine_SMILES = ['C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1',

'CCCCP(CCCC)CCCC',

'CP(C1=CC=CC=C1)C2=CC=CC=C2',

'COC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(OC)C=C2)C3=CC=C(OC)C=C3)C=C1',

'FC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(F)C=C2)C3=CC=C(F)C=C3)C=C1',

'FC(F)(F)C1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C2)C3=CC=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C3)C=C1',

'CC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(C=C2)C)C3=CC=C(C=C3)C)C=C1',

'C1(P(C2CCCCC2)C3CCCCC3)CCCCC1',

'C1(P(C2=CC=CO2)C3=CC=CO3)=CC=CO1',

'CC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)C=C1',

'ClC1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=C(Cl)C=C2)C3=CC=C(Cl)C=C3)C=C1',

'CN(C1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)C=C1)C']

solvent_NAMES = ['dimethyl formamide', 'tetrahydrofuran', 'acetonitrile', 'toluene', 'ethyl acetate']

substrate_concentrations = [0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20]

azadicarb_equivs = [1.1, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7, 1.9]

phos_equivs = [1.1, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7, 1.9]

temperatures = [5, 15, 25, 35, 45]

# (1) Define a dictionary of components

components = {'azadicarboxylate':azadicarboxylate_SMILES,

'phosphine':phosphine_SMILES,

'solvent':solvent_NAMES,

'substrate_concentration':substrate_concentrations,

'azadicarb_equiv':azadicarb_equivs,

'phos_equiv':phos_equivs,

'temperature':temperatures}

# (2) Define a dictionary of desired encodings

# Note: if an encoding is not specified OHE will be used

encoding = {'substrate_concentration':'numeric',

'azadicarb_equiv':'numeric',

'phos_equiv':'numeric',

'temperature':'numeric'}

# (3) Instatiate BO_express to automatically build the reaction space

bo = BO_express(components,

encoding,

batch_size=5,

target='yield')

We can use EDBO utilities to visualize the azadicarboxylates and phosphines.

from edbo.chem_utils import ChemDraw

for SMILES in [azadicarboxylate_SMILES, phosphine_SMILES]:

cdx = ChemDraw(SMILES, 6)

cdx.show()

One-hot-encoding categorical features: This gives our search space 180,000 possible experiments and a 27 dimensional encoding.

bo.obj.domain.head()

| azadicarboxylate=CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | azadicarboxylate=CC(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)C)=O)=O)C | … | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | … |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | … |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | … |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | … |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | … |

bo.reaction.base_data[bo.reaction.index_headers].head()

| azadicarboxylate_index | phosphine_index | solvent_index | substrate_concentration_index | … | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | dimethyl formamide | 0.05 | … |

| 1 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | dimethyl formamide | 0.05 | … |

| 2 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | dimethyl formamide | 0.05 | … |

| 3 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | dimethyl formamide | 0.05 | … |

| 4 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | dimethyl formamide | 0.05 | … |

There are also built-in methods to automatically generate cheminformatics reaction encodings and read in precomputed descriptor matrices for each component (we won’t cover this topic here but this is how you can use hand curated or DFT based descriptors). For example, let’s say you wanted to use Mordred fingerprints to encode all of the reaction components. This is easy to do by either using SMILES strings or chemical names for the reaction components.

encoding = {'azadicarboxylate':'mordred', # Compute mordred descriptors

'phosphine':'mordred',

'solvent':'resolve', # Search the NIH database for the structure

'substrate_concentration':'numeric',

'azadicarb_equiv':'numeric',

'phos_equiv':'numeric',

'temperature':'numeric'}

bo = BO_express(components,

encoding,

batch_size=5,

target='yield')

SMILES strings and chemical names: This gives our search space 180,000 possible experiments and a 644 dimensional encoding.

bo.obj.domain.head()

| azadicarboxylate_ABC | azadicarboxylate_SpMax_A | azadicarboxylate_SpMAD_A | azadicarboxylate_VR2_A | … | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.350891 | 0.64384 | 0 | 0.194388 | … |

| 1 | 0.350891 | 0.64384 | 0 | 0.194388 | … |

| 2 | 0.350891 | 0.64384 | 0 | 0.194388 | … |

| 3 | 0.350891 | 0.64384 | 0 | 0.194388 | … |

| 4 | 0.350891 | 0.64384 | 0 | 0.194388 | … |

bo.reaction.base_data[bo.reaction.index_headers].head()

| azadicarboxylate_SMILES_index | phosphine_SMILES_index | solvent_SMILES_index | substrate_concentration_index | … | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | CN(C)C=O | 0.05 | … |

| 1 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | CN(C)C=O | 0.05 | … |

| 2 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | CN(C)C=O | 0.05 | … |

| 3 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | CN(C)C=O | 0.05 | … |

| 4 | CC(C)(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | CN(C)C=O | 0.05 | … |

Dealing with errors: An obvious question here is what happens when EDBO cannot generate an encoded search space due to an error? Importantly, the BO_express class also attempts to handle exceptions due to erroneous SMILES strings or chemical names that can not be resolved by spawning an bot to help.

Name can not be resolved:

from edbo.bro import BO_express

components={'aryl_halide':['chlorobenzene','iodobenzene','bromobenzene', 'NOT-A-REAL-MOLECULE'],

'base':['DBU', 'MTBD', 'potassium carbonate', 'potassium phosphate'],

'solvent':['THF', 'Toluene', 'DMSO', 'DMAc'],

'ligand': ['c1ccc(cc1)P(c2ccccc2)c3ccccc3',

'C1CCC(CC1)P(C2CCCCC2)C3CCCCC3',

'CC(C)c1cc(C(C)C)c(c(c1)C(C)C)c2ccccc2P(C3CCCCC3)C4CCCCC4']}

encoding={'aryl_halide':'resolve',

'base':'ohe',

'solvent':'resolve',

'ligand':'smiles'}

bo = BO_express(components, encoding)

Spawns a dialog with edbo bot:

edbo bot: For help try BO_express.help() or see the documentation page.

edbo bot: Building reaction space...

edbo bot: The following names could not be converted to SMILES strings:

(3) NOT-A-REAL-MOLECULE

edbo bot: Would you like to enter a SMILES string or one-hot-encode this component?

~ Use ohe instead

edbo bot: OK one-hot-encoding aryl_halide...

SMILES error:

from edbo.bro import BO_express

components={'aryl_halide':['chlorobenzene','iodobenzene','bromobenzene'],

'base':['DBU', 'MTBD', 'potassium carbonate', 'potassium phosphate'],

'solvent':['THF', 'Toluene', 'DMSO', 'DMAc'],

'ligand': ['c1ccc(cc1)P(c2ccccc2)c3ccccc3',

'C1CCC(CC1)P(C2CCCCC2)C3CCCCC3',

'NOT-A-REAL-SMILES-STRING']}

encoding={'aryl_halide':'resolve',

'base':'ohe',

'solvent':'resolve',

'ligand':'smiles'}

bo = BO_express(components, encoding)

Spawns a dialog with edbo bot:

edbo bot: For help try BO_express.help() or see the documentation page.

edbo bot: Building reaction space...

edbo bot: Mordred failed to encode one or more SMILES strings in ligand. Would you like to one-hot-encode instead?

~ no

edbo bot: Identifying problematic SMILES string(s)...

edbo bot: Mordred failed with the following string(s):

(2) NOT-A-REAL-SMILES-STRING

edbo bot: ligand was removed from the reaction space. Resolve issues with SMILES string(s) and try again.

Running the optimizer

OK, back to the Mitsunobu reaction. Now that we have defined the search space we can start the optimization. We will follow exactly the same procedure that we did in post I. First, let’s gather some initial experimental data (tn this case I wouldn’t advise using clustering to select points - since the search space is a 180000 x 644 dimensional matrix and kmeans is instance based this will require quite a bit of memory).

bo.init_sample(seed=0) # Initialize with a random sample

bo.export_proposed('round0.csv') # Write the proposed experiments to a CSV

bo.get_experiments() # Get a DataFrame of the proposed experiments

| azadicarboxylate_SMILES_index | phosphine_SMILES_index | … | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 91036 | O=C(OCC1=CC=CC=C1)/N=N/C(OCC2=CC=CC=C2)=O | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | … |

| 59238 | CC(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)C)=O)=O)C | CN(C1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)C=C1)C | … |

| 149078 | O=C(N1CCCCC1)/N=N/C(N2CCCCC2)=O | CN(C1=CC=C(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)C=C1)C | … |

| 31550 | CC(OC(/N=N/C(OC(C)C)=O)=O)C | C1(P(C2=CC=CC=C2)C3=CC=CC=C3)=CC=CC=C1 | … |

| 155877 | CN(C(/N=N/C(N(C)C)=O)=O)C | CP(C1=CC=CC=C1)C2=CC=CC=C2 | … |

Next, we would go into the lab and run the proposed experiments. You can also save your workspace and load it later when you are ready for the next round.

bo.save()

Since this is an example we will “run” the experiments by just assigning random values to the experiment yields. Once we have experimental data we can load the results and use EDBO to select the next round of experiments.

bo.load() # Load BO (if you exited)

bo.add_results('round0.csv') # Add results via CSV

bo.run() # Fit model and optimize acquisition function

The random results corresponding to the initial experiments are the following:

bo.obj.results_input()

| … | substrate_concentration | azadicarb_equiv | phos_equiv | temperature | yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| external0 | … | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 5 |

| external1 | … | 0.333333 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 10 |

| external2 | … | 0 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 40 |

| external3 | … | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| external4 | … | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 3 |

In order to select the next experiments the optimizer has to fit the model and optimize the acquisition function. This is a pretty computationally expensive venture and the computation time scales with the size of the search space. For this example, it took 115 seconds on my laptop to select the next batch of 5 experiments. Next, we may want to run some preliminary analysis.

Check out the model’s fit: Notice that the model does not fit the data perfectly. This is because there is not enough data to overcome the surrogate model priors when computing the posterior predictive distribution.

bo.model.regression()

Model mean and variance for selected experiments: We can reason about how exploitative (high posterior mean) exploratory (high posterior variance) the model is for the selected points. In this example notice that the first point selected by the optimizer does not have the highest predicted yield. Rather the posterior variance is large - these figures give a 95% prediction interval ($2\sigma$) including a maximum yield of ~58%.

bo.acquisition_summary()

| … | substrate_concentration | azadicarb_equiv | phos_equiv | temperature | predicted yield | variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 134104 | … | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 18.8457 | 377.263 |

| 129604 | … | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 21.0823 | 307.17 |

| 141624 | … | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16.7992 | 337.949 |

| 136999 | … | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 21.7643 | 242.817 |

| 147504 | … | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21.9171 | 242.673 |

Plot the acquisition function: If we dig into the acquisition module we can also plot the acquisition function projection which results in the selection of each experiment.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fig, ax = plt.subplots(5,1, figsize=(10, 10), )

i = 0

for p in bo.acq.function.projections:

# Acquisition Function on X indices

ax[i].plot(range(len(p)), p, color='C' + str(i))

ax[i].set_ylabel('EI' + str(i))

# ArgMax

top = np.argmax(p).flatten()[0]

ax[i].scatter([top], [p[top]], s=100, color='black')

i += 1

plt.xlabel('X')

plt.show()

Finally, we can export the proposed experiments to collect the next round of data, rinse and repeat.

bo.export_proposed('round1.csv') # Write the proposed experiments to a CSV

Up next

In the final post on Bayesian reaction optimization using EDBO, we will investigate how you can use EDBO for your own research! Whether you are interested in optimizing the yield or selectivity of a reaction, finding a new ligand structure, or choosing the best model architecture for modeling chemical reaction data you can use Bayesian optimization to help find an optimal configuration for your task.